This text is an adaptation of a fragment of our guidebook to Ephesus: "The Secrets of Ephesus".

The archaeological finds from Ephesus can be seen in different locations around the world. We have already shown you the Ephesian artefacts on display in the Ephesos Museum in Vienna. However, the earliest findings, excavated between 1867 and 1905, were taken to the British Museum in London. The person responsible for the British involvement in Ephesus was John Turtle Wood, who went to this area of the Ottoman Empire to design railway stations for Smyrna-Aydın railway. Before we show you the treasures from Ephesus in the British Museum collections, let us take a closer look at the history of the earliest archaeological research of this ancient city.

Even though the location of ancient Ephesus had never been a secret, only the 19th century saw the beginning of in-depth research of this ancient site. The history of archaeological research in Ephesus dates back to 1863 when British engineer John Turtle Wood, sponsored by the British Museum, began searching for the remains of the Temple of Artemis. All the European travellers who visited Ephesus from the 16th to the 19th century tried to locate this temple in vain, as it had disappeared entirely from view more than half a millennium before.

In 1858, John Turtle Wood arrived at Ephesus with a completely different task, but while staying in the area, he became fascinated by the history of the Artemision and decided to start looking for its remains. In 1863, he relinquished his commission as an engineer and began the search with the support of the British Museum that granted him a permit and a small allowance for expenses. In return, the museum expected to get the property rights for any antiquities that Wood might discover in Ephesus. His work attracted the attention of some prominent personalities of the period and had visits from Sultan Abdülaziz, one of Queen Victoria's sons – Prince Arthur, and even the discoverer of Troy, Heinrich Schliemann.

His search started in the area of the ancient city between the Koressos and Pion Hills, where numerous ancient structures were still visible above the ground. He struck gold while excavating the theatre area where an inscription was buried. This was, in fact, a document of a benefaction given to the city by a Roman, C. Vibius Salutaris in 103–104 CE. As part of his benefaction, Salutaris funded a procession through the city every two weeks that began and ended at the temple of Artemis, passing various monumental structures of the city on the way. This inscription was an excellent tip for Wood: as it described gold and silver statuettes carried from the Artemision through the Magnesian Gate into the theatre. That meant that the Artemision had to be situated outside the walls of the ancient city.

The idea that the temple was located outside the city, beyond its walls, was not that fresh. It was first proposed by the British traveller and architect Edward Falkener. In 1842, he started on a tour of Europe, continuing through Asia Minor, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt. He spent a fortnight sketching the ancient ruins of Ephesus during his trip. His thoughts about the Artemision were published in 1862 as the book "Ephesus and the Temple of Diana". This is still an excellent collection of drawings and attempted reconstructions of Ephesian buildings. However, Falkener placed the Artemision near the harbour of Panormos, so his assumptions were incorrect.

Nevertheless, Wood had no academic background in history and possibly did not know about Falkener's suggestion. Instead, he started the search for a paved road, i.e. the ancient processional way that would begin at the gate and reach the temple. He found it in 1867 and followed its course. He described his discoveries in a letter to John Winter Jones, dated to the 22nd of December 1868: "I have succeeded in opening up and exploring more than 1000 feet of the way leading northward from the Magnesian Gates, along the whole length of which I have found the pieces of the Portico which, I presume, may be that built by Damianus, as described by Philostratus. This Portico has fairly led me on to the Ground demonstrated on the Plan submitted to the Trustees, as that upon which the Temple of Diana might have stood. For a distance of more than 700 feet of the way at present opened up, there is a continuous line of tombs and sarcophagi which appear to have been substituted for the pieces of the Portico for a considerable length on the East side while those on the West side remain intact sarcophagi being placed between them."

This way, he reached the Artemision area, where he discovered the wall of the temple. He proceeded to excavate the site and, on the 31st of December 1869, found the temple buried deep beneath five meters of soil and sand, as a consequence of the temple's construction on torrential alluvium. Not much was left of the temple, though, as it had served as a quarry for construction materials in the Byzantine period. Wood excavated many sculptures and architectural fragments that he sent to London along with the Salutaris inscription.

Wood dedicated the next five years to the excavations in this area. However, after the initial discovery of pavement of the temple, further work did not bring many significant results, and disappointed Wood had the excavations stopped in 1874. During his stay in Ayasuluk, Wood suffered from fever, encountered bandits, survived earthquakes and injuries, and endured hot summers and cold winters. The swampy area of the Artemision did not help to improve his well-being. In 1874 his health was devastated, his funding cut short, and he decided to return home to London where he spent the rest of his life, giving lectures and receiving a pension in recognition of his discoveries.

The British researchers came back to Ephesus between 1904 and 1905 when excavations were conducted by David George Hogarth, under the auspices of the British Museum. As a result of these works, the foundations of the Artemision were dug out. Moreover, the chronology of construction phases on this site was established. The remains of the temple, discovered during these excavations, were collected and are now on display in the British Museum in London.

You can find out much more about the ancient city of Ephesus in our guidebook "The Secrets of Ephesus".

- Round-mouthed jug found in the foundations of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, East Greek, probably made on Samos, about 650-625 BCE

- Lid from a pyxis (cosmetic box) with animals and a cuirass

- Two terracotta plaques, showing a woman or a goddess, and a bronze hawk and duck

- Marble female head from the Temple of Artemis, about 550-520 BCE

- Marble female head from the Temple of Artemis, about 550-520 BCE

- Marble sanctuary lamp, with three oil compartments, from the Temple of Artemis, about 600 BCE

- Gold, silver and terracotta ornaments, dedicated to the goddess Artemis by worshippers in her sanctuary at Ephesus, dating to about 650-600 BCE

- Statuette of Artemis, Greek, 2nd-1st century BCE, said to be from Ephesus

- Terracotta figure of Artemis of Ephesus, Roman, 1st century CE

- Bronze statuette of the goddess Diana of Ephesus, Roman, the 1st or the 2nd century CE

- Sculpted drum from the Artemision

Round-mouthed jug found in the foundations of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, East Greek, probably made on Samos, about 650-625 BCE

With the jug are electrotypes (copies) of the 19 electrum coins found in it, constituting the oldest known hoard of coins. They belong to the earliest period of coinage, soon after its invention in this part of the Greek world.

Some believe that coinage did not begin until about 600 BCE. The Ephesus coins, however, cannot be later than the burial of the jug, which is unlikely to have taken place long after its manufacture.

Lid from a pyxis (cosmetic box) with animals and a cuirass

Made in Corinth about 650-630 BCE, from the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus.

Two terracotta plaques, showing a woman or a goddess, and a bronze hawk and duck

The plaques are from the 7th century BCE, and the bronze animals from the 6th century BCE. They are from the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus.

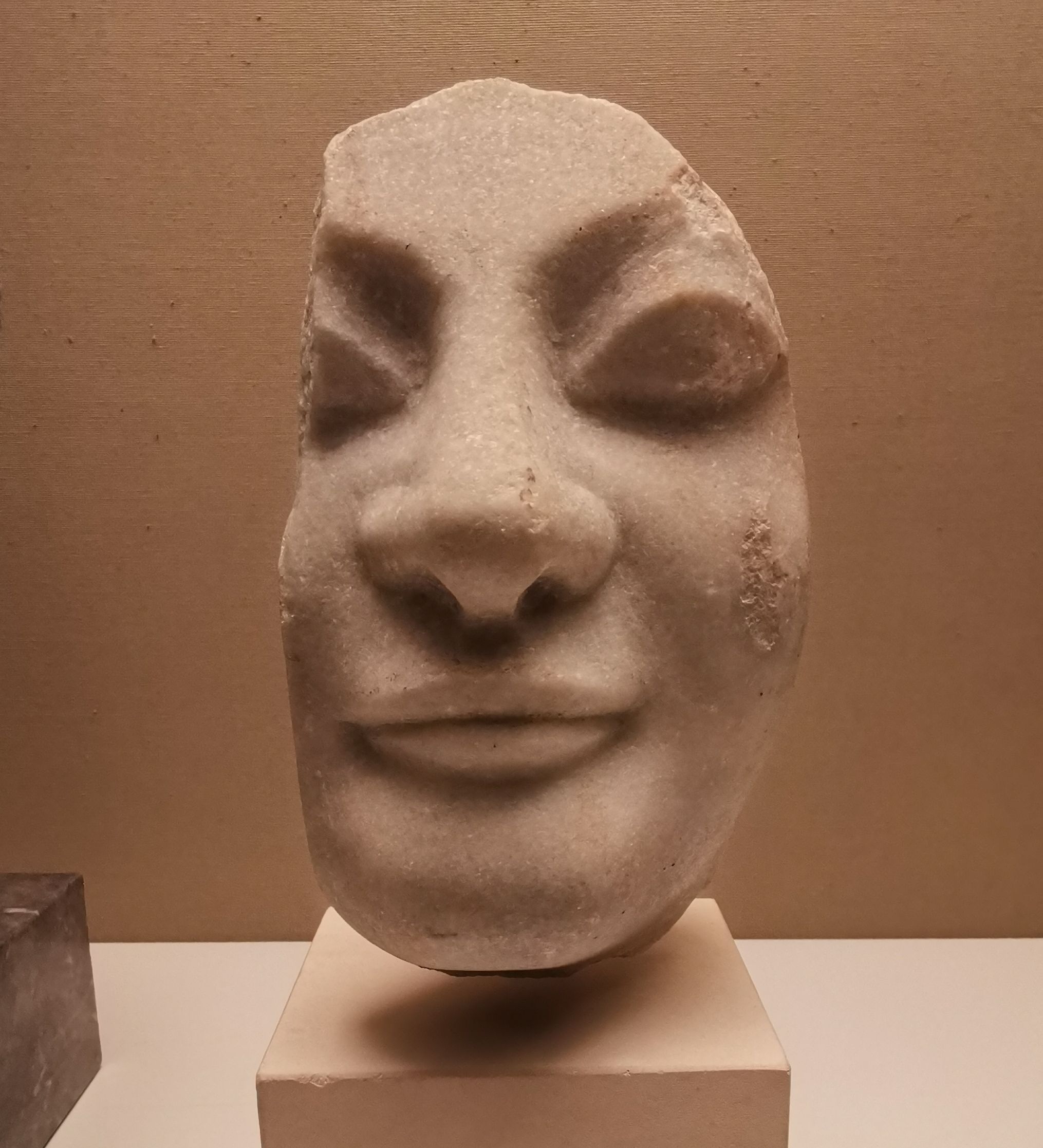

Marble female head from the Temple of Artemis, about 550-520 BCE

This head formed a part of a figure that was carved onto a column drum. It may have come from a procession of worshippers carrying offerings to Artemis. This head has a disc earring, a diadem and traces of the original colour survive.

Marble female head from the Temple of Artemis, about 550-520 BCE

This head is carved in the East Greek style, with fleshy facial features and long, almond-shaped eyes. The pupils would have been added in paint. It is unclear whether this head belonged to the carved column drums or to a frieze with a flat background.

Marble sanctuary lamp, with three oil compartments, from the Temple of Artemis, about 600 BCE

The lamp would originally have been hung up by chains threaded through the three pierced holes.

Gold, silver and terracotta ornaments, dedicated to the goddess Artemis by worshippers in her sanctuary at Ephesus, dating to about 650-600 BCE

Statuette of Artemis, Greek, 2nd-1st century BCE, said to be from Ephesus

Terracotta figure of Artemis of Ephesus, Roman, 1st century CE

The Ephesian Artemis, with her stiff, upright pose, is known from many ancient copies of the cult statue. Her close-fitting garments were highly decorated. She is an Asiatic fertility goddess totally distinct from the Greek deity of the same name.

Bronze statuette of the goddess Diana of Ephesus, Roman, the 1st or the 2nd century CE

Probably dedicated in the sanctuary of Diana (Artemis) at Ephesus.

Sculpted drum from the Artemision

The carved relief on the base of a column of the Hellenistic Artemision, the most complete surviving remnant of the temple's once lavish sculptural decoration.

Photos courtesy of Glenn Maffia.